Today is the 72nd Anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima. This is the third section of the series, Original Child Bomb, some of which explores why it's important to acknowledge this anniversary each year. The past is present. The decision-making process that led to the dropping of the bomb has had a direct influence on both conventional US military strategy and US views about its nuclear arsenal.

The first part in the series can be found here (part 1). The second can be found here (part 2).

The first part in the series can be found here (part 1). The second can be found here (part 2).

The Conventional Narrative

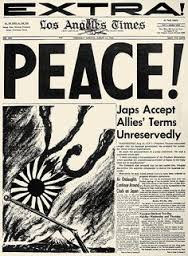

August 6th, 1945: the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki saved countless lives.

This is the story we in the US are continually told: because

of the fierce and almost suicidal fighting on Okinawa by the Japanese

(true), and the appearance of kamikaze pilots in the war at sea (true), many in

the Pentagon assumed that an invasion of the Japanese home islands would cost

the lives of up to a million US soldiers. The story goes on to say that, because

the US made the decision to drop two atomic bombs, Japan immediately surrendered

- saving countless US and Japanese lives. As Ward Wilson said in Five Myths about Nuclear Weapons (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2013): "If

nuclear weapons were a religion, Hiroshima would be the first miracle." (p

23)

This is the story we in the US are continually told: because

of the fierce and almost suicidal fighting on Okinawa by the Japanese

(true), and the appearance of kamikaze pilots in the war at sea (true), many in

the Pentagon assumed that an invasion of the Japanese home islands would cost

the lives of up to a million US soldiers. The story goes on to say that, because

the US made the decision to drop two atomic bombs, Japan immediately surrendered

- saving countless US and Japanese lives. As Ward Wilson said in Five Myths about Nuclear Weapons (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2013): "If

nuclear weapons were a religion, Hiroshima would be the first miracle." (p

23)

The lesson learned - and the legacy for military

strategy - was that overwhelming force caused the capitulation of the enemy. So,

the question is: did the weapons work in the way American history says they did?

Five Months of

Saturation Bombing

|

| Tokyo Firebombing |

|

| Tokyo Firebombing |

Between March 9-19, 1945, there was the saturation bombing

of Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, Yokohama, and Kawasaki. In late May, the saturation

bombing continued on Tokyo. The NY Times headline on May 30, 1945 read:

"Fifty-One square miles burned out in six B-29 attacks on Tokyo." (Dower, p 183) These raids were in

keeping with the Allied strategy of saturation bombing in Germany, specifically

targeting civilian populations, from 1942 through the end of the war.

|

| Tokyo Firebombing (mother & child) |

Franklin D. Roosevelt had, in 1939, beseeched all nations to refrain from “inhuman barbarism,” of attacking civilian

centers. In the recent past, he noted such assaults had “resulted in the

maiming and in the death of thousands of defenseless men, women, and children.” (The German bombing of Guernica, The Japanese bombing of Shanghai) But by 1942, targeting civilian populations had become a routine Allied strategy.

Callousness on Both Sides

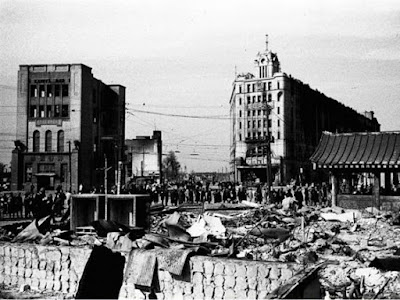

|

| Tokyo |

|

| Hirohito walks through ruins of Tokyo |

The

US Decision

Meanwhile, back in the US, the Interim Committee (a

secret high-level group created in May 1945 by United States Secretary of

War, Henry L. Stimson, at the urging of leaders of the Manhattan

Project and with the approval of Harry S. Truman to advise on

matters pertaining to nuclear energy) were meeting to decide what to do

with the nuclear weapon, the product of The Manhattan Project. The project had

been started with the belief that the scientists were in a race against

Germany. But through intelligence reports, it was clear that by 1944 Germany

did not have the capabilities to build a bomb. So, who were we continuing to

build the bomb for?

|

| Oppenheimer with General Leslie Groves at Trinity Site |

Oppenheimer himself was for the use of the weapon because, in his own convoluted thinking, he believed that "if the bomb is to make war impossible, it must have a very strong effect." So, like the military, he sought peace - even an ultimate global peace - through overwhelming use of force. He also said this: "The elements of surprise and terror are intrinsic to the use of nuclear weapons." (Dower, p 211) Between Stimson, on the government side, and Oppenheimer, on the production side, it was almost unanimous that the bomb be used as a test on some city that was relatively untouched - a test for both physical and psychological damage.

Surprisingly, there was a lone dissenter on the Interim Committee.

Under Secretary of the Navy, Ralph Bard, who wrote the "Memorandum on the use of the S-1 Bomb," argued for warning the Japanese ahead of time of the exact nature of the bomb, fearing the decision to drop it on civilians would have

an adverse effect on "the position of the US as a great humanitarian

nation." (Dower, p 232)

Surprisingly, there was a lone dissenter on the Interim Committee.

Under Secretary of the Navy, Ralph Bard, who wrote the "Memorandum on the use of the S-1 Bomb," argued for warning the Japanese ahead of time of the exact nature of the bomb, fearing the decision to drop it on civilians would have

an adverse effect on "the position of the US as a great humanitarian

nation." (Dower, p 232)

When the decision was made, the actual invasion plans had already

been drawn up, and were set to begin in November of 1945 on a southern island,

followed by an invasion force into the Tokyo-Yokohama area around March of 1946.

Knowing what they knew about Japanese

resistance during the bombings, and how few actual cities were left standing, why

the extreme haste in using the bombs? By the fall, starvation alone, and the

unrest it would have created for the government, would have brought the

Japanese to the table. Surrender could have happened without the bombs, Soviet

entry into the war, or an allied invasion.

By this time, because of the massive incendiary bombing of

civilians (for years, on all fronts, by everyone),

reliance on overwhelming force had become gospel and second nature. In May of

1945, the Interim Committee decided that "the number of people that would

be killed by the bomb would not be greater in general magnitude than the number

already killed in fire raids." (Dower, p 225)

In the documentary The Fog of War, former US Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara, recalled that General Curtis LeMay, the man who relayed the Presidential order to drop the nuclear bombs on Japan, had said: "If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals…"

|

| Hiroshima aftermath |

In the documentary The Fog of War, former US Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara, recalled that General Curtis LeMay, the man who relayed the Presidential order to drop the nuclear bombs on Japan, had said: "If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals…"

"And I think he’s

right," McNamara said. "He, and I’d say I, were behaving as war

criminals. LeMay recognized that what he was doing would be thought immoral if

his side had lost. But what makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you

win?"

|

| Enola Gay flying from explosion over Hiroshima |

Next:

Finishing the history of the decision making process (the Soviet angle, partisan politics, the bomb as the first shot fired in the Cold War, and the spread of the Bomb Myth with help from the Japanese High Command)

No comments:

Post a Comment